"The free communication of thought

and opinion is one of the most precious rights of man; every citizen may

therefore speak, write and print freely."

(French National Assembly, 1789)

The Origin of the Book

This article can be found here

Papyrus:

This article can be found here

Writing is a system of linguistic symbols which permit one to transmit and conserve information. Writing appears to have developed between the 7th millennium BC and the 4th millennium BC, first in the form of early mnemonic symbols which became a system of ideograms or pictographs through simplification. The oldest known forms of writing were thus primarily logographic in nature. Latersyllabic and alphabetic (or segmental) writing emerged.

Silk, in China, was also a base for writing. Writing was done with brushes. Many other materials were used as bases: bone, bronze, pottery, shell, etc. In India, for example, dried palm tree leaves were used; in Mesoamerica another type of plant, Amate. Any material which will hold and transmit text is a candidate for use in bookmaking.

The book is also linked to the desire of humans to create lasting records. Stones could be the most ancient form of writing, but wood would be the first medium to take the guise of a book. The wordsbiblos and liber first meant "fibre inside of a tree". In Chinese, the character that means book is an image of a tablet of bamboo. Wooden tablets (Rongorongo) were also made on Easter Island.

Clay: Clay tablets were used in Mesopotamia in the 3rd millennium BC. The calamus, an instrument in the form of a triangle, was used to make characters in moist clay. The tablets were fired to dry them out. At Nineveh, 22,000 tablets were found, dating from the 7th century BC; this was the archive and library of the kings of Assyria, who had workshops of copyists and conservationists at their disposal. This presupposes a degree of organization with respect to books, consideration given to conservation, classification, etc. Tablets were used right up until the 19th century in various parts of the world, including Germany, Chile, and the Saharan Desert.

Papyrus:

Papyrus was first manufactured in Egypt as far back as the third millennium BC. In the first centuries BC and AD, papyrus scrolls gained a rival as a writing surface in the form of parchment, which was prepared from animal skins. Sheets of parchment were folded to form quires from which book-form codices were fashioned.Early Christian writers soon adopted the codex form, and in the Græco-Roman world, it became common to cut sheets from papyrus rolls to form codices.

Codices were an improvement on the papyrus scroll, as the papyrus was not pliable enough to fold without cracking and a long roll, or scroll, was required to create large-volume texts. Papyrus had the advantage of being relatively cheap and easy to produce, but it was fragile and susceptible to both moisture and excessive dryness. Unless the papyrus was of perfect quality, the writing surface was irregular, and the range of media that could be used was also limited.

Papyrus was replaced in Europe by the cheaper, locally produced products parchment and vellum, of significantly higher durability in moist climates, though Henri Pirenne's connection of its disappearance with the Muslim overrunning of Egypt is contended. Its last appearance in the Merovingian chancery is with a document of 692, though it was known in Gaul until the middle of the following century. The latest certain dates for the use of papyrus are 1057 for a papal decree* (typically conservative, all papal "bulls" were on papyrus until 1022), under Pope Victor II, and 1087 for an Arabic document. Its use in Egypt continued until it was replaced by more inexpensive paper introduced by Arabs. By the 12th century, parchment and paper were in use in the Byzantine Empire, but papyrus was still an option.

Papyrus was made in several qualities and prices; these are listed, with minor differences, both by Pliny and Isidore of Seville.

Until the middle of the 19th century, only some isolated documents written on papyrus were known. They did not contain literary works. The first discovery of papyri rolls in modern days was made at Herculaneum in 1752. Before that date, the only papyri known were a few surviving from medieval times.

*A papal bull is a particular type of letters patent or charter issued by a Pope of the Catholic Church. It is named after the lead seal (bulla) that was appended to the end in order to authenticate it.

Papal bulls were originally issued by the pope for many kinds of communication of a public nature, but by the 13th century, papal bulls were only used for the most formal or solemn of occasions.

Manufacturing:

Papyrus is made from the stem of the papyrus plant, Cyperus papyrus. The outer rind is first removed, and the sticky fibrous inner pith is cut lengthwise into thin strips of about 40 cm (16 in) long. The strips are then placed side by side on a hard surface with their edges slightly overlapping, and then another layer of strips is laid on top at a right angle. The strips may have been soaked in water long enough for decomposition to begin, perhaps increasing adhesion, but this is not certain. The two layers possibly were glued together. While still moist, the two layers are hammered together, mashing the layers into a single sheet. The sheet is then dried under pressure. After drying, the sheet is polished with some rounded object, possibly a stone or seashell or round hardwood.

Sheets could be cut to fit the obligatory size or glued together to create a longer roll. A wooden stick would be attached to the last sheet in a roll, making it easier to handle.

The Art of the Book - Elif Ayiter

Medieval Europe. One of the darkest periods known to mankind: Pestilence and plague, darkness and fear, witch-hunts and illiteracy roam the land. It is a world where most people seldom leave their place of birth for any distance longer than 10 miles, where few people even live beyond the age of 30. In this inhospitable milieu, secluded in the scriptoria of cold monasteries, under the light of feeble oil lamps, mittened against the biting cold; some of the greatest book designers that ever lived, created some of the most beautiful books the world has ever seen. The colophons of the their creations are testimony to their short lives since most of the books that they worked upon were only completed in several of their brief lifetimes, one scribe replacing the other over decades. We call these beautiful books Illuminated Manuscripts.

An illuminated manuscript is a manuscript in which the text is supplemented by the addition of decoration or illustration, such as decorated initials, borders and miniatures. In the strictest definition of the term, an illuminated manuscript only refers to manuscripts decorated with gold or silver. However, in both common usage and modern scholarship, the term is now used to refer to any decorated manuscript.

An illuminated manuscript is a manuscript in which the text is supplemented by the addition of decoration or illustration, such as decorated initials, borders and miniatures. In the strictest definition of the term, an illuminated manuscript only refers to manuscripts decorated with gold or silver. However, in both common usage and modern scholarship, the term is now used to refer to any decorated manuscript.

The earliest surviving substantive illuminated manuscripts are from the period AD 400 to 600, primarily produced in Ireland, Italy and other locations on the European continent. The meaning of these works lies not only in their inherent art history value, but in the maintenance of a link of literacy. Had it not been for the (mostly monastic) scribes of late antiquity, the entire content of western heritage literature from Greece and Rome could have perished. The very existence of illuminated manuscripts as a way of giving stature and commemoration to ancient documents may have been largely responsible for their preservation in an era when barbarian hordes had overrun continental Europe.

The majority of surviving manuscripts are from the Middle Ages, although many illuminated manuscripts survive from the 15th century Renaissance, along with a very limited number from late antiquity. The majority of these manuscripts are of a religious nature. However, especially from 13th century onward, an increasing number of secular texts were illuminated. Most illuminated manuscripts were created as codices, although many illuminated manuscripts were rolls or single sheets. A very few illuminated manuscript fragments survive on papyrus. Most medieval manuscripts, illuminated or not, were written on parchment (most commonly calf, sheep, or goat skin) or vellum (calf skin). Beginning in the late Middle Ages manuscripts began to be produced on paper.

Illuminated manuscripts are the most common item to survive from the Middle Ages. They are also the best surviving specimens of medieval painting. Indeed, for many areas and time periods, they are the only surviving examples of painting.

The Scriptorium

A scriptorium (plural scriptoria) was a room devoted to the hand-lettered copying of manuscripts. Before the invention of printing by moveable type, a scriptorium was a normal adjunct to a library. In the monasteries, the scriptorium was a room, rarely a building, set apart for the professional copying of manuscripts. The director of a monastic scriptorium was the armarius or scrittori, who provided the scribes with their materials and directed the process. Rubrics and illuminations were added by a separate class of specialists.

A scriptorium (plural scriptoria) was a room devoted to the hand-lettered copying of manuscripts. Before the invention of printing by moveable type, a scriptorium was a normal adjunct to a library. In the monasteries, the scriptorium was a room, rarely a building, set apart for the professional copying of manuscripts. The director of a monastic scriptorium was the armarius or scrittori, who provided the scribes with their materials and directed the process. Rubrics and illuminations were added by a separate class of specialists.

Techniques

Illumination was a complex and frequently costly process. As such, it was usually reserved for special books: an altar Bible, for example. Wealthy people often had richly illuminated "books of hours" made, which set down prayers appropriate for various times in the liturgical day.

Illumination was a complex and frequently costly process. As such, it was usually reserved for special books: an altar Bible, for example. Wealthy people often had richly illuminated "books of hours" made, which set down prayers appropriate for various times in the liturgical day.

Papyrus, the writing surface of choice in Antiquity, became prohibitively expensive as commercial supplies dried up propably through over-harvesting and was replaced by parchment and vellum. During the 7th through the 9th centuries, many earlier parchment manuscripts were scrubbed and scoured to be ready for rewriting. Such overwritten parchment manuscripts, where the original text has begun faintly to show through, are called palimpsests. Many of the works of Antiquity often said to have been preserved in the monasteries were only preserved as palimsests. In the 13th century paper began to displace parchment. As paper became cheaper, parchment was reserved for elite uses of documents that were of particular importance.

In the making of an illuminated manuscript, the text was usually written first. Sheets of parchment or vellum, animal hides specially prepared for writing, were cut down to the appropriate size. After the general layout of the page was planned (e.g., initial capital, borders), the page was lightly ruled with a pointed stick, and the scribe went to work with ink-pot and either sharpened quill feather or reed pen.

In the making of an illuminated manuscript, the text was usually written first. Sheets of parchment or vellum, animal hides specially prepared for writing, were cut down to the appropriate size. After the general layout of the page was planned (e.g., initial capital, borders), the page was lightly ruled with a pointed stick, and the scribe went to work with ink-pot and either sharpened quill feather or reed pen.

The script depended on local customs and tastes. The sturdy Roman letters of the early Middle Ages gradually gave way to cursive scripts such as Uncial and half-Uncial, especially in the British Isles, where distinctive scripts such as insular majuscule and insular minuscule developed. Stocky, richly textured blackletter was first seen around the 13th century and was particularly popular in the later Middle Ages.

When the text was complete, the illustrator set to work. Complex designs were planned out beforehand, probably on wax tablets, the sketch pad of the era. The design was then traced onto the vellum (possibly with the aid of pinpricks or other markings, as in the case of the Lindisfarne Gospels).

The Book of Hours

A Book of Hours is the most common type of surviving medieval illuminated manuscript. Each Book of Hours is unique, but all contain a collection of texts, prayers and psalms, along with appropriate illustrations, to form a convenient reference for Christian worship and devotion. The Books of Hours were composed for use by lay people who wished to incorporate elements of monasticism into their devotional life. Reciting the hours typically centered upon the recitation or singing of a number of psalms, accompanied by set prayers. The most famous of these were created by the Limbourg Brothers for the Duc de Berry at the beginning of the 15th century.

A Book of Hours is the most common type of surviving medieval illuminated manuscript. Each Book of Hours is unique, but all contain a collection of texts, prayers and psalms, along with appropriate illustrations, to form a convenient reference for Christian worship and devotion. The Books of Hours were composed for use by lay people who wished to incorporate elements of monasticism into their devotional life. Reciting the hours typically centered upon the recitation or singing of a number of psalms, accompanied by set prayers. The most famous of these were created by the Limbourg Brothers for the Duc de Berry at the beginning of the 15th century.

Books of Hours for the Duc de Berry. Top: Les Tres belles Heures du Duc de Berry, bottom: Les Tres Riches Heures du Duc de Berry.

Music scores (antiphoner) from late 16th Century.

As Medieval Europe metamorphosed into a new age through the Renaisance these beautiful hand crafted books inevitably gave way to the onset of a new technology: The printing press, whereby books could be mass produced and became everyday objects of use rather than the jewels hidden in the libraries of Popes, Dukes and Kings as they had been for many many centuries. The change was gradual and although the beauty of the illuminated manuscript was forever lost another beauty came to replace it: The mastery of the grid and of type.

Letterpress - Elif Ayiter

This article can be found here

Incunabula

An incunabulum is a book, single sheet, or image that was printed — not handwritten — before the year 1501 in Europe. These are usually very rare and fragile items whose nature can only be verified by experts. The origin of the word is the Latin incunabula for "swaddling clothes", used by extension for the infancy or early stages of something. The first recorded use of incunabula as a printing term is in a pamphlet by Bernard von Mallinckrodt, "Of the rise and progress of the typographic art", published in Cologne in 1639, which includes the phrase prima typographicae incunabula, "the first infancy of printing". The term came to denote the printed books themselves from the late 17th century.

An incunabulum is a book, single sheet, or image that was printed — not handwritten — before the year 1501 in Europe. These are usually very rare and fragile items whose nature can only be verified by experts. The origin of the word is the Latin incunabula for "swaddling clothes", used by extension for the infancy or early stages of something. The first recorded use of incunabula as a printing term is in a pamphlet by Bernard von Mallinckrodt, "Of the rise and progress of the typographic art", published in Cologne in 1639, which includes the phrase prima typographicae incunabula, "the first infancy of printing". The term came to denote the printed books themselves from the late 17th century.

There are two types of incunabula: the xylographic (made from a single carved or sculpted block for each page) and the typographic (made with movable type on a printing press in the style of Johann Gutenberg). Many authors reserve the term incunabulum for the typographic ones only. The end date for identifying a book as an incunabulum is convenient, but was chosen arbitrarily. It does not reflect any notable developments in the printing process around the year 1500. Incunabula usually refers to the earliest printed books, completed at a time when some books were still being hand-copied. The gradual spread of printing ensured that there was great variety in the texts chosen for printing and the styles in which they appeared. Many early typefaces were modelled on local forms of writing or derived from the various European forms of Gothic script, but there were also some derived from documentary scripts (such as most of Caxton's types), and, particularly in Italy, types modelled on humanistic hands. These humanistic typefaces are often used today, barely modified, in digital form.

Incunabula from Germany. Late 15th century

Incunabula from Italy. End of 15th century.

Incunabula from France. End of 15th century

Printers tended to congregate in urban centres where there were scholars, ecclesiastics, lawyers, nobles and professionals who formed their major customer-base. Standard works in Latin inherited from the medieval tradition formed the bulk of the earliest printing, but as books became cheaper, works in the various vernaculars (or translations of standard works) began to appear. Famous incunabula include the Gutenberg Bible of 1455 and the Liber Chronicarum of Hartmann Schedel, printed by Anton Koberger in 1493. Other well-known incunabula printers were Albrecht Pfister of Bamberg, Günther Zainer of Augsburg, Johann Mentelin of Strasbourg and William Caxton of Bruges and London.

The design of the books shows all the characteristics of a transitional period: Although they still resemble their medieval counterparts where ornamentation, initials and bordering are concerned they are certainly no longer as dark and dense as the medieval illuminated manuscripts: Already we see a move towards whiter, lighter pages. Some of this can also be attributed to the import of paper manufacturing technologies which lessened the cost of book production. While columns were already present during earlier times, during the incunabula book designers far greater use of them for design purposes. The gridding which set type necessitated technologically caused the books to adhere to a grid system, yet another novelty in design.

The Introduction of Rag Paper

The word paper comes from the ancient Egyptian writing material called papyrus, which was woven from papyrus plants. Papyrus was produced as early as 3000 BC in Egypt, and in ancient Greece and Rome. Further north, parchment or vellum, made of processed sheepskin or calfskin, replaced papyrus, as the papyrus plant requires subtropical conditions to grow. In China, documents were ordinarily written on bamboo, making them very heavy and awkward to transport. Silk was sometimes used, but was normally too expensive to consider. Indeed, most of the above materials were rare and costly.

Some historians speculate that paper was the key element in global cultural advancement. According to this theory, Chinese culture was less developed than the West in ancient times prior to the Han Dynasty because bamboo, while abundant, was a clumsier writing material than papyrus; Chinese culture advanced during the Han Dynasty and preceding centuries due to the invention of paper; and Europe advanced during the Renaissance due to the introduction of paper and the printing press.

Paper remained a luxury item through the centuries, until the advent of steam-driven paper making machines in the 19th century, which could make paper with fibres from wood pulp. Although older machines predated it, the Fourdrinier paper making machine became the basis for most modern papermaking. Together with the invention of the practical fountain pen and the mass produced pencil of the same period, and in conjunction with the advent of the steam driven rotary printing press, wood based paper caused a major transformation of the 19th century economy and society in industrialized countries. Before this era a book or a newspaper was a rare luxury object and illiteracy was normal. With the gradual introduction of cheap paper, schoolbooks, fiction, non-fiction, and newspapers became slowly available to nearly all the members of an industrial society. Cheap wood based paper also meant that keeping personal diaries or writing letters ceased to be reserved to a privileged few. The office worker or the white-collar worker was slowly born of this transformation, which can be considered as a part of the industrial revolution.

During the incunabula period, Europeans used rags to make paper by the following method: the rags were cut into small pieces; fermented; ground by watermill; and scooped into a mould to dry. Therefore handmade paper does not have a uniform thickness; it varies in thickness according to the mesh of the mould. If held against the light, the thinner part of handmade paper appears brighter, and it is possible to detect thick lines spaced several centimeters apart, as well as thin lines closely spaced crossing the thick lines at a right angle. The thick lines are referred to as the "chain line" and the thin lines the "wire line."

Johannes Gutenberg

(1398 – 1468) was a German goldsmith and inventor who achieved fame for his invention of the technology of printing with movable types during 1447. Gutenberg has often been credited as being the most influential and important person of all times, with his invention occupying similar status. The A&E Network ranked him at #1 on their "People of the Millennium" countdown in 1999.

(1398 – 1468) was a German goldsmith and inventor who achieved fame for his invention of the technology of printing with movable types during 1447. Gutenberg has often been credited as being the most influential and important person of all times, with his invention occupying similar status. The A&E Network ranked him at #1 on their "People of the Millennium" countdown in 1999.

The Gutenberg Bible. 1455

Block printing, whereby individual sheets of paper were pressed into wooden blocks with the text and illustrations carved into them, was first recorded in Chinese history, and was in use in East Asia long before Gutenberg. By the 12th and 13th centuries, many Chinese libraries contained tens of thousands of printed books. The Chinese and Koreans knew about moveable metal type at the time, but because of the complexity of the movable type printing it was not as widely used as in Renaissance Europe.

It is not clear whether Gutenberg knew of these existing techniques, or invented them independently, although the former is considered unlikely because of the substantial differences in technique. Some also claim that the Dutchman Laurens Janszoon Coster was the first European to invent movable type.

Gutenberg certainly introduced efficient methods into book production, leading to a boom in the production of texts in Europe — in large part, owing to the popularity of the Gutenberg Bibles, the first mass-produced work, starting on February 23, 1455. Even so, Gutenberg was a poor businessman, and made little money from his printing system.

Gutenberg began experimenting with metal typography after he had moved from his native town of Mainz to Strasbourg (then in Germany, now France) around 1430. Knowing that wood-block type involved a great deal of time and expense to reproduce, because it had to be hand-carved, Gutenberg concluded that metal type could be reproduced much more quickly once a single mould had been fashioned.

In 1455, Gutenberg demonstrated the power of the printing press by selling copies of a two-volume Bible (Biblia Sacra) for 300 florins each. This was the equivalent of approximately three years' wages for an average clerk, but it was significantly cheaper than a handwritten Bible that could take a single monk 20 years to transcribe. The one copy of the Biblia Sacra dated 1455 went to Paris, and was dated by the binder. (View the Gutenberg Bible)

The Korean Jikji: Oldest movable type.1377

The Gutenberg Bibles surviving today are sometimes called the oldest surviving books printed with movable type — although actually, the oldest such surviving book is the Jikji, published in Korea in 1377. However, it is still notable, in that the print technology that produced the Gutenberg Bible marks the beginning of a cultural revolution unlike any that followed the development of print culture in Asia. The Gutenberg Bible lacks many print features that modern readers are accustomed to, such as pagination, word spacing, indentations, and paragraph breaks.

The Golden canon of page construction

Raúl Rosarivo, in his "Typographical Divine Proportion", first published in 1947, was the first to analyze Renaissance books with the help of compass and ruler and concluded that Gutenberg applied the golden canon of page construction to his work. His work and assertion that Gutenberg used the "golden number" or "secret number" to establish the harmonic relationships between the diverse parts of a work, was analyzed by experts at the Gutenberg Museum and re-published in the Gutenberg Jahrbuch, its official magazine. Historian John Man points out that Gutenberg's Bible's page was based on the golden section shape, based on the irrational number 0.618.... (a ratio of 5:8) and that the printed area also had that shape.

Albrecht Duerer

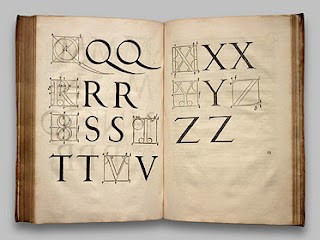

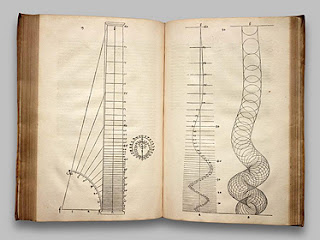

(1471 – 1528) was a German painter, wood carver, engraver, and mathematician. Born in Nuremberg, Germany, he is best known for his woodcuts in series, including the Apocalypse (1498), two series on the crucifixion of Christ, the Great Passion (1498–1510) and the Little Passion (1510–1511) as well as many of his individual prints, such as Knight, Death, and the Devil (1513), Saint Jerome in his Study (1514) and Melencholia I (1514). In this latter work appears the Dürer's magic square. His Four Horsemen of the Apocalypse (1497–1498), part of the Apocalypse series, is also celebrated. He is also known for his numerous self-portraits. He is important for the history of graphic design in that he spent considerable time on the geometry of letters as well as book design. Best known of the books on the geometry of letters is Dürer's Unterweysung der Messung [A Course on the Art of Measurement]. The text is printed in a form of textura, a black letter style. The book presents the principles of perspective developed in Renaissance Italy, applying them to architecture, painting, and lettering. Dürer's designs of Roman capital letters, shown below, demonstrate how they can be created using geometrical aids.

Pages from Albrecht Duerer famous book on design fundamentals: "De Symmetria" (Unterweysung der Messung), 1525

What Are Incunabula?

The table above is a cross-tabulation of incunabula according to the year of publication and where they were printed. The table shows that 68% of incunabula were published in Italy or Germany and about 83% were published from 1481 onwards. Works written in Latin account for 72% of incunabula and cities where they were published in order of number of titles are: Venice, Paris, Rome, Cologne, Lyons, Leipzig, Strassburg, Milan and Augsburg. 56 percent of all incunabula were printed in these nine cities. Currently, there are 26,550 known incunabula titles and they are collected in every region of the world. In Great Britain, there are about 14,000 titles, in the United States, about 13,000 titles, and in Italy and Germany, about 12,000 titles. There are about 370 titles of incunabula kept in Japan and 13 of those are held by the NDL. Libraries with the largest collections of incunabula are the British Library, the Bavarian State Library, the National Library of France, the Bodleian Library, the Vatican Apostolica Library (Biblioteca Apostolica Vaticana), and the Library of Congress in the United States.

A History of the Typewriter

The concept of a typewriter dates back at least to 1714, when Englishman Henry Mill filed a vaguely-worded patent for "an artificial machine or method for the impressing or transcribing of letters singly or progressively one after another." But the first typewriter proven to have worked was built by the Italian Pellegrino Turri in 1808 for his blind friend Countess Carolina Fantoni da Fivizzano; unfortunately, we do not know what the machine looked like, but we do have specimens of letters written by the Countess on it. (For details, see Michael Adler's excellent 1973 book The Writing Machine. Carey Wallace's 2010 novel The Blind Contessa's New Machine is based on the relationship between the Countess and Turri.)

Numerous inventors in Europe and the U.S. worked on typewriters in the 19th century, but successful commercial production began only with the "writing ball" of Danish pastor Rasmus Malling-Hansen (1870). This well-engineered device looked rather like a pincushion. Nietzsche's mother and sister once gave him one for Christmas. He hated it.

Much more influential, in the long run, was the Sholes & Glidden Type Writer, which began production in late 1873 and appeared on the American market in 1874.

The Sholes & Glidden had limited success, but its successor, the Remington, soon became a dominant presence in the industry.

The Sholes & Glidden, like many early typewriters, is an understroke or "blind" writer: the typebars are arranged in a circular basket under the platen (the printing surface) and type on the bottom of the platen. This means that the typist (confusingly called a "typewriter" herself in the early days) has to lift up the carriage to see her work. Another example of an understroke typebar machine is the Caligraph of 1880, the second typewriter to appear on the American market. This Caligraph has a "full" keyboard -- separate keys for lower- and upper-case letters. Click here to read more about the Caligraph.

The Smith Premier (1890) is another example of a full-keyboard understroke typewriter which was very popular in its day. Click here to read more and see the machine.

The QWERTY keyboard came to be called the "Universal" keyboard, as the alternative keyboards fought a losing battle against the QWERTY momentum. (For more on QWERTY and to learn why "QWERTY is cool," visit Darryl Rehr's site The QWERTY Connection.) But not all early typewriters used the QWERTY system, and many did not even type with typebars. Case in point: the ingenious Hammond, introduced in 1884. The Hammond came on the scene with its own keyboard, the two-row, curved "Ideal" keyboard -- although Universal Hammonds were also soon made available. The Hammond prints from a type shuttle -- a C-shaped piece of vulcanized rubber. The shuttle can easily be exchanged when you want to use a different typeface. There is no cylindrical platen as on typebar typewriters; the paper is hit against the shuttle by a hammer.

The Hammond gained a solid base of loyal customers. These well-engineered machines lasted, with a name change to Varityper and electrification, right up to the beginning of the word-processor era.

Other machines typing from a single type element rather than typebars included the gorgeous Crandall (1881) ...

... and the practical Blickensderfer.

The effort to create a visible rather than "blind" machine led to many ingenious ways of getting the typebars to the platen. Examples of early visible writers include the Williams and the Oliver. The Daugherty Visible of 1891 was the first frontstroke typewriter to go into production: the typebars rest below the platen and hit the front of it. With the Underwood of 1895, this style of typewriter began to gain ascendancy. The most popular model of early Underwoods, the #5, was produced by the millions. By the 1920s, virtually all typewriters were "look-alikes": frontstroke, QWERTY, typebar machines printing through a ribbon, using one shift key and four banks of keys. (Some diehards lingered on. The huge Burroughs Moon-Hopkins typewriter and accounting machine was a blind writer that was manufactured, amazingly enough, until the late 1940s.)

Let's return for a moment to the 19th century. The standard price for a typewriter was $100 -- several times the value of a good personal computer today, when we adjust for inflation. There were many efforts to produce cheaper typewriters. Most of these were index machines: the typist first points at a letter on some sort of index, then performs another motion to print the letter. Obviously, these were not heavy-duty office machines; they were meant for people of limited means who needed to do some occasional typing. An example is the "American" index typewriter, which sold for $5. Index typewriters survived into the 20th century as children's toys; one commonly found example is the "Dial" typewriter made by Marx Toys in the 1920s and 30s

|

Contemporary era

The demands of the British and Foreign Bible Society (founded 1804), the American Bible Society (founded 1816), and other non-denominational publishers for enormously large and impossibly inexpensive runs of texts led to numerous innovations. The introduction of steam printing presses a little before 1820, closely followed by new steam paper mills, constituted the two most major innovations. Together, they caused book prices to drop and the number of books to increase considerably. Numerous bibliographic features, like the positioning and formulation of titles and subtitles, were also affected by this new production method. New types of documents appeared later in the 19th century: photography, sound recording and film.

Typewriters and eventually computer based word processors and printers let people print and put together their own documents.

Among a series of developments that occurred in the 1990s, the spread of digital multimedia, which encodes texts, images, animations, and sounds in a unique and simple form was notable for the book publishing industry. Hypertext further improved access to information. Finally, the internet lowered production and distribution costs.

E-Resources

It is difficult to predict the future of the book. A good deal of reference material, designed for direct access instead of sequential reading, as for example encyclopedias, exists less and less in for the form of books and increasingly on the web. Leisure reading materials are increasingly published in e-reader formats.

Although electronic books, or e-books, had limited success in the early years, and readers were resistant at the outset, the demand for books in this format has grown dramatically, primarily because of the popularity of e-reader devices and as the number of available titles in this format has increased. Another important factor in the increasing popularity of the e-reader is its continuous diversification. Many e-readers now support basic operating systems, which facilitate email and other simple functions. The iPad is the most obvious example of this trend, but even mobile phones can host e-reading software.

E-book readers such as the Sony Reader, Barnes & Noble's Nook, and the Amazon Kindle have increased in popularity each time a new upgraded version is released. The Kindle in particular has captured public attention not only for the quality of the reading experience but also because users can access books (as well as periodicals and newspapers) wirelessly online (a feature now available in all other e-reader devices). Apple has also entered this arena with applications for the iPhone and iPad which enable e-book reading.

How the Paperback Changed Literature

The story about the first Penguin paperbacks may be apocryphal, but it is a good one. In 1935, Allen Lane, chairman of the eminent British publishing house Bodley Head, spent a weekend in the country with Agatha Christie. Bodley Head, like many other publishers, was faring poorly during the Depression, and Lane was worrying about how to keep the business afloat. While he was in Exeter station waiting for his train back to London, he browsed shops looking for something good to read. He struck out. All he could find were trendy magazines and junky pulp fiction. And then he had a “Eureka!” moment: What if quality books were available at places like train stations and sold for reasonable prices—the price of a pack of cigarettes, say?

Lane went back to Bodley Head and proposed a new imprint to do just that. Bodley Head did not want to finance his endeavor, so Lane used his own capital. He called his new house Penguin, apparently upon the suggestion of a secretary, and sent a young colleague to the zoo to sketch the bird. He then acquired the rights to ten reprints of serious literary titles and went knocking on non-bookstore doors. When Woolworth’s placed an order for 63,500 copies, Lane realized he had a viable financial model.

Lane’s paperbacks were cheap. They cost two and a half pence, the same as ten cigarettes, the publisher touted. Volume was key to profitability; Penguin had to sell 17,000 copies of each book to break even.

The first ten Penguin titles, including The Mysterious Affair at Styles by Agatha Christie, A Farewell to Arms by Ernest Hemingway and The Unpleasantness at the Bellona Club by Dorothy Sayers, were wildly successful, and after just one year in existence, Penguin had sold over three million copies.

Penguin’s graphic design played a large part in the company’s success. Unlike other publishers, whose covers emphasized the title and author of the book, Penguin emphasized the brand. The covers contained simple, clean fonts, color-coding (orange for fiction, dark blue for biography) and that cute, recognizable bird. The look helped gain headlines. The Sunday Referee declared “the production is magnificent” and novelist J. B. Priestley raved about the “perfect marvels of beauty and cheapness.” Other publishing houses followed Penguin’s lead; one, Hutchinson, launched a line called Toucan Books.

With its quality fare and fine design, Penguin revolutionized paperback publishing, but these were not the first soft-cover books. The Venetian printer and publisher Aldus Manutius had tried unsuccessfully to publish some in the 16th century, and dime novels, or “penny dreadfuls” –lurid romances published in double columns and considered trashy by the respectable houses, were sold in Britain before the Penguins. Until Penguin, quality books, and books whose ink did not stain one's hands, were available only in hardcover.

In 1937, Penguin expanded, adding a nonfiction imprint called Pelican, and publishing original titles. Pelican’s first original nonfiction title was George Bernard Shaw’s The Intelligent Woman’s Guide to Socialism, Capitalism, Sovietism & Fascism. It also published left-leaning Penguin Specials such as Why Britain Is at Warand What Hitler Wants that sold widely. As these titles reveal, Penguin played a role in politics as well as in literature and design, and its left-leaning stance figured into Britain’s war and postwar efforts. After the Labour Party came to office in 1945, one of the party leaders declared that the accessibility of left-leaning reading during the war helped his party succeed: “After the WEA [Workers’ Educational Association] it was Lane and his Penguins which did most to get us into office at the end of the war.” The ousted Conservative Party opened an exhibition on the unfortunate spread of Socialism and included photographs of those responsible, including one of Lane.

During World War II, Penguins, which were small enough to be stowed in the pocket of a uniform, were carried by soldiers, and they were chosen for the Services Central and the Forces Book Clubs. In 1940, Lane launched an imprint for youngsters, Puffin Picture Books, which children facing evacuation could carry with them to their new, uncertain homes. During the times of paper rationing, Penguin fared better than its competitors, and the books’ simple design allowed Penguin to easily accommodate the typographic restrictions. Author and professor Richard Hoggart, who served in the war, noted that the books “became a signal: if the back trouser pocket bulged in that way that usually indicated a reader.” They were also carried in the bag in which gas masks were carried and above the left knee of battle dress.

The United States adopted the Penguin model in 1938 with the creation of Pocket Books. The first Pocket Book title was The Good Earth by Pearl Buck, and it was sold in Macy’s. Unlike Penguin, Pocket Books were lavishly illustrated with bright covers. Other U.S. paperback companies followed Pocket’s lead, and like Penguin, the books were carried by soldiers. One soldier, who had been shot and was waiting in a foxhole for help, “spent the hours before help came reading Willa Cather’s Death Comes for the Archbishop, the Saturday Evening Postreported in 1945. “He grabbed it the day before under the delusion that it was a murder mystery, but he discovered, to his amazement, that he liked it anyway.” Avon, Dell, Ace and Harlequin published genre fiction and new literary titles, including novels by Henry Miller and John Steinbeck.

Allen Lane stated that he “believed in the existence…of a vast reading public for intelligent books at a low price, and staked everything on it.” Seventy-five years later, we find ourselves in a situation not unlike Lane’s in 1935. Publishers are facing plummeting sales, and many are attempting to launch new models, chasing the dream to be the next Penguin. New e-readers have been unveiled recently, including the iPad, Kindle and Nook. Digital editions are cheaper than paperbacks—you can buy the latest literary fiction for $9.99—but they come with a hefty start-up price. The basic iPad costs $499, and the two versions of the Kindle are priced at $259 and $489. Not exactly the price of a pack of cigarettes—or, to use a healthier analogy, a pack of gum.

E- Book Vs the Physical Book - Which has a better place in History, and Will the E- Book Take Over?

I have highlighted sections from this book "A Malignant Self Love" by Sam Vaknin

1. What is a Book?

UNESCO's uninspiring, arbitrary, and ungrounded definition of "book" is:

"Non-periodical printed publication of at least 49 pages excluding covers."

But a book, above all else, is a medium. It encapsulates information (of one kind or another) and conveys it across time and space. Moreover, as opposed to common opinion, it is - and has always been - a rigidly formal affair. Even the latest "innovations" are nothing but ancient wine in sparkling new bottles.

Consider the scrolling protocol. Our eyes and brains are limited readers-decoders. There is only that much that the eye can encompass and the brain interpret. Hence the need to segment data into cognitively digestible chunks. There are two forms of scrolling - lateral and vertical. The papyrus, the broadsheet newspaper, and the computer screen are three examples of the vertical scroll - from top to bottom or vice versa. The e-book, the microfilm, the vellum, and the print book are instances of the lateral scroll - from left to right (or from right to left, in the Semitic languages).

In many respects, audio books are much more revolutionary than e-books. They do not employ visual symbols (all other types of books do), or a straightforward scrolling method. E-books, on the other hand, are a throwback to the days of the papyrus. The text cannot be opened at any point in a series of connected pages and the content is carried only on one side of the (electronic) "leaf". Parchment, by comparison, was multi-paged, easily browseable, and printed on both sides of the leaf. It led to a revolution in publishing and to the print book. All these advances are now being reversed by the e-book. Luckily, the e-book retains one innovation of the parchment - the hypertext. Early Jewish and Christian texts (as well as Roman legal scholarship) was written on parchment (and later printed) and included numerous inter-textual links. The Talmud, for example, is made of a main text (the Mishna) which hyperlinks on the same page to numerous interpretations (exegesis) offered by scholars throughout generations of Jewish learning.

Another distinguishing feature of books is portability (or mobility). Books on papyrus, vellum, paper, or PDA - are all transportable. In other words, the replication of the book's message is achieved by passing it along and no loss is incurred thereby (i.e., there is no physical metamorphosis of the message). The book is like a perpetuum mobile. It spreads its content virally by being circulated and is not diminished or altered by it. Physically, it is eroded, of course - but it can be copied faithfully. It is permanent.

Not so the e-book or the CD-ROM. Both are dependent on devices (readers or drives, respectively). Both are technology-specific and format-specific. Changes in technology - both in hardware and in software - are liable to render many e-books unreadable. And portability is hampered by battery life, lighting conditions, or the availability of appropriate infrastructure (e.g., of electricity).

Summary:

Essentially, E- Books work differently to physical books, due to the way we read. E- Books involve reading vertically, and physical books involve reading Left to Right.

Physical books have been around for thousands of years, nothing has naturally evolved from them that has been more successful. E – Books rely on technology, thus could become dated at a certain point.

2. The Constant Content Revolution

Every generation applies the same age-old principles to new "content-containers". Every such transmutation yields a great surge in the creation of content and its dissemination. The incunabula (the first printed books) made knowledge accessible (sometimes in the vernacular) to scholars and laymen alike and liberated books from the scriptoria and "libraries" of monasteries. The printing press technology shattered the content monopoly. In 50 years (1450-1500), the number of books in Europe surged from a few thousand to more than 9 million! And, as McLuhan has noted, it shifted the emphasis from the oral mode of content distribution (i.e., "communication") to the visual mode.

E-books are threatening to do the same. "Book ATMs" will provide Print on Demand (POD) services to faraway places. People in remote corners of the earth will be able to select from publishing backlists and front lists comprising millions of titles. Millions of authors are now able to realize their dream to have their work published cheaply and without editorial barriers to entry. The e-book is the Internet's prodigal son. The latter is the ideal distribution channel of the former. The monopoly of the big publishing houses on everything written - from romance to scholarly journals - is a thing of the past. In a way, it is ironic. Publishing, in its earliest forms, was a revolt against the writing (letters) monopoly of the priestly classes. It flourished in non-theocratic societies such as Rome, or China - and languished where religion reigned (such as in Sumeria, Egypt, the Islamic world, and Medieval Europe).

With e-books, content will once more become a collaborative effort, as it has been well into the Middle Ages. Authors and audience used to interact (remember Socrates) to generate knowledge, information, and narratives. Interactive e-books, multimedia, discussion lists, and collective authorship efforts restore this great tradition. Moreover, as in the not so distant past, authors are yet again the publishers and sellers of their work. The distinctions between these functions is very recent. E-books and POD partially help to restore the pre-modern state of affairs.

Summary:

E - Books appeal best to small authors. Writers can create novels and publish them themselves, making the whole process much easier. They are no longer having to invest money into publishers.

E- Books let people all around the world access a whole library of books, through a giant form of database.

3. Literature for the Millions

The plunge in book prices, the lowering of barriers to entry due to new technologies and plentiful credit, the proliferation of publishers, and the cutthroat competition among booksellers was such that price regulation (cartel) had to be introduced. Net publisher prices, trade discounts, list prices were all anti-competitive inventions of the 19th century, mainly in Europe. They were accompanied by the rise of trade associations, publishers organizations, literary agents, author contracts, royalties agreements, mass marketing, and standardized copyrights.

The sale of print books over the Internet can be conceptualized as the continuation of mail order catalogues by virtual means. But e-books are different. They are detrimental to all these cosy arrangements. Legally, an e-book may not be considered to constitute a "book" at all. Existing contracts between authors and publishers may not cover e-books. The serious price competition they offer to more traditional forms of publishing may end up pushing the whole industry to re-define itself. Rights may have to be re-assigned, revenues re-distributed, contractual relationships re-thought. Moreover, e-books have hitherto been to print books what paperbacks are to hardcovers - re-formatted renditions. But more and more authors are publishing their books primarily or exclusively as e-books. E-books thus threaten hardcovers and paperbacks alike. They are not merely a new format. They are a new mode of publishing.

Summary:

E - Books have created an industry that at the moment is hard to define its future, due to them legally not being seen as books. The change between hardback and paperback made little difference, due to the book itself still being a physical object, and pricing not varying much.

E- Books are an entirely different form of communication method, which will completely change the market.

IV. Intellectual Pirates and Intellectual Property

The first-ever print runs were tiny by our standards and costly by any standard. Gutenberg produced fewer than 200 copies of his eponymous and awe-inspiring Bible and died a broken and insolvent man. Other printers followed suit when they failed to predict demand (by readers) and supply (by authors who acted as their own publishers, pirates, underground printers, and compilers of unauthorized, wild editions of works).

Confronted with the vagaries of this new technology, for many decades printer-publishers confined themselves to pornographic fiction, religious tracts, political pamphlets, dramaturgy, almanacs, indulgences, contracts, and prophecies – in other words, mostly disposable trash. As most books were read aloud – as a communal, not an individual experience – the number of copies required was limited.

Not surprisingly, despite the technological breakthroughs that coalesced to form the modern printing press, printed books in the 17th and 18th centuries were derided by their contemporaries as inferior to their laboriously hand-made antecedents and to the incunabula. One is reminded of the current complaints about the new media (Internet, e-books), its shoddy workmanship, shabby appearance, and the rampant piracy. The first decades following the invention of the printing press, were, as the Encyclopedia Britannica puts it "a restless, highly competitive free for all ... (with) enormous vitality and variety (often leading to) careless work".

There were egregious acts of piracy - for instance, the illicit copying of the Aldine Latin "pocket books", or the all-pervasive piracy in England in the 17th century (a direct result of over-regulation and coercive copyright monopolies). Shakespeare's work was published by notorious pirates and infringers of emerging intellectual property rights.

Later, the American colonies became the world's centre of industrialized and systematic book piracy. Confronted with abundant and cheap pirated foreign books, local authors resorted to freelancing in magazines and lecture tours in a vain effort to make ends meet.

Pirates and unlicenced - and, therefore, subversive - publishers were prosecuted under a variety of monopoly and libel laws (and, later, under national security and obscenity laws). There was little or no difference between royal and "democratic" governments. They all acted ruthlessly to preserve their control of publishing. John Milton wrote his passionate plea against censorship, Areopagitica, in response to the 1643 licencing ordinance passed by Parliament. The revolutionary Copyright Act of 1709 in England established the rights of authors and publishers to reap the commercial fruits of their endeavours exclusively, though only for a prescribed period of time.

Books – at times with their authors – were repeatedly burned as the ultimate form of purging: Luther’s works were cast into the flames and, in retaliation, he did the same to Catholic opera; the oeuvres of Rousseau, Servetus, Hernandez, and, of course, of Jewish authors during the Nazi era all suffered an identical fate. Indeed, the Internet is the first text-based medium (at least at its inception) to have evaded censorship and regulation altogether.

Summary:

Traditionally, books have been copied and pirated. The internet is constantly used for piracy with films, games etc... So the same could happen for E - Books. The music industry has taken a massive hit due to illegal downloads, could the same be said for the publication industry?

In the past, publishers and authors have had to worry about supply and demand. Due to nothing physical being made, the same can't be said for E - Books.

7. The More it Changes

The more it changes, the more it stays the same. If the history of the book teaches us anything it is that there are no limits to the ingenuity with which publishers, authors, and booksellers, re-invent old practices. Technological and marketing innovations are invariably perceived as threats - only to be adopted later as articles of faith. Publishing faces the same issues and challenges it faced five hundred years ago and responds to them in much the same way. Yet, every generation believes its experiences to be unique and unprecedented. It is this denial of the past that casts a shadow over the future. Books have been with us since the dawn of civilization, millennia ago. In many ways, books constitute our civilization. Their traits are its traits: resilience, adaptation, flexibility, self re-invention, wealth, communication. We would do well to accept that our most familiar artifacts - books - will never cease to amaze us.

Summary:

Communication is always going to be made as easy as possible, as it is something natural to us, and has been for thousands of years. Our very own existance relies on publications and literature. Our past is known through it, and our future will be held within it. Why does it matter if it is an E - Book or a publication, if you strictly enjoy the process of absorbing information. If you enjoy the physical process of reading a book, then this can be entirely different.